Ellen Marie Saethre-McGuirk, Queensland University of Technology

Thanks to the increasing accessibility of technology, many of us will try to capture the grandeur of the natural world with our phone cameras. One of the attractions is sharing images on social media and publicly staking our claim to that experience.

A quick glance at Instagram hashtags reveals over 90 million photos tagged #landscape, around 50 million #sunrise photos and over 180 million tagged #sunset. There are 40 million #trees, nearly 90 million #clouds and about 190 million #beach photos.

But our use of platforms such as Instagram is not only changing our relationship to nature (some people have even died taking selfies in perilous places), it is also changing how we frame and experience nature.

Earlier this year a man died falling off rocks in Western Australia in the pursuit of an image. And in July three social media personalities died after falling off a Canadian waterfall.

While such deaths are rare, many travellers and adventure seekers seem to be drawn towards more remote experiences of nature in lieu of the downtrodden tourist track, using Instagram as a source for visually inspiring and enticing sites. Police warn people to avoid an imminently crumbling cliff in New South Wales, while amateur photographers continue to ignore signs and fences.

Read more: The deadly selfie game – the thrill to end all thrills

Just as nature can harm people, people can harm nature. Two of the social media personalities who died in Canada had spent a week in jail for violating US national park regulations. In Tasmania, professional photographers have warned of the damage that could be done to the environment by hordes of people chasing views they have seen on social media. And in Esperance, Western Australia, people are trying to figure out how to capitalise on an influx of visitors driven by its discovery by Instagram users.

As part of my research, I have looked at how we present experiences of nature through new technology and social media. Most photos share traits we might describe as “a social media aesthetic”. Think of leafy paths, mountain vistas, sunrises and sunsets – often with filters or the same kinds of photo composition.

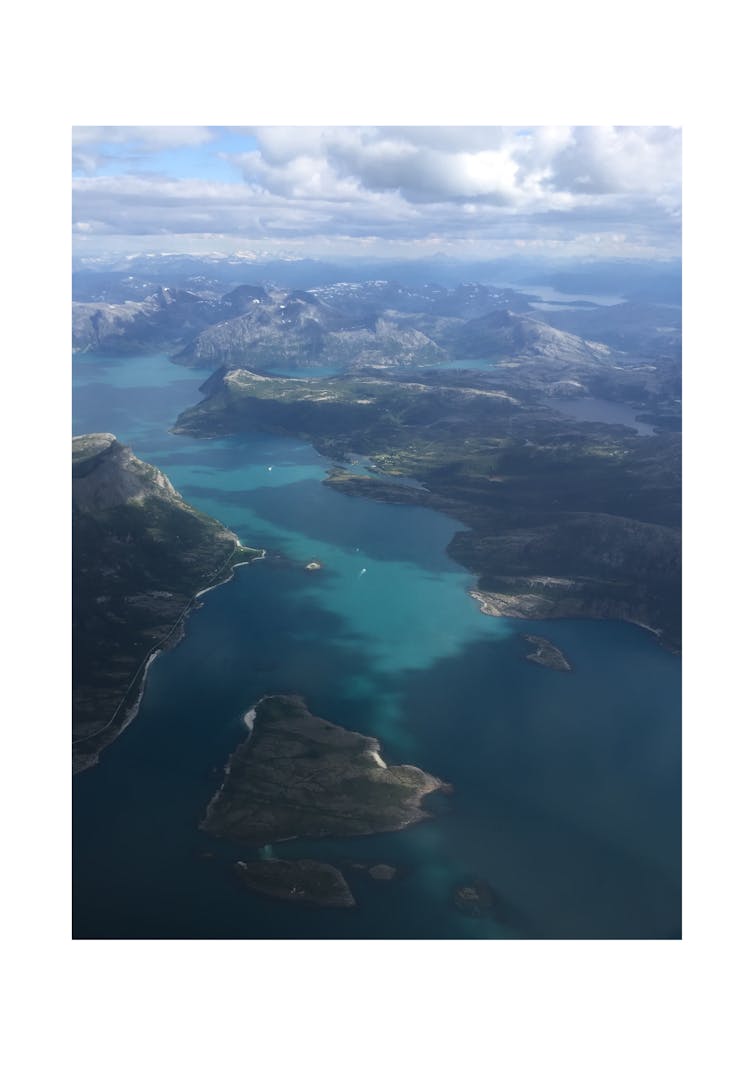

In my art-as-research project, the exhibition Norwegian Sublime, I used these “Instagram standards” to take photos at different locations in Norway, both well-known places such as Svalbard and less famous islands like Tomma of the Helgeland archipelago. Although they seem remote and difficult to get to, I deliberately chose places that were frequently visited and where tourism was controlled, as well as places that were literally right next to main thoroughfares, showing how the perfect picture of untouched mountain solitude can be at anyone’s fingertips. In fact, those less exotic sites around you might actually hide some of the most striking nature.

Together, the images link up art photography and the history of photography with diminutive tell-tale signs typical of iPhone and social media photography. I framed clouds with Instagram squares, referencing art photography and weather studies from the early 1900s. I gave aerial photography a contemporary twist by taking photos from the window of today’s commercial flights, forever shuttling tourists back and forth.

In other photos, I left those patches of surfaces that are difficult to photograph with a phone, such as reflective, wet leaves and shiny rocks, washed out and bleak. And even in the seemingly romantically remote locations I intentionally left speckled signs of people in the frame.

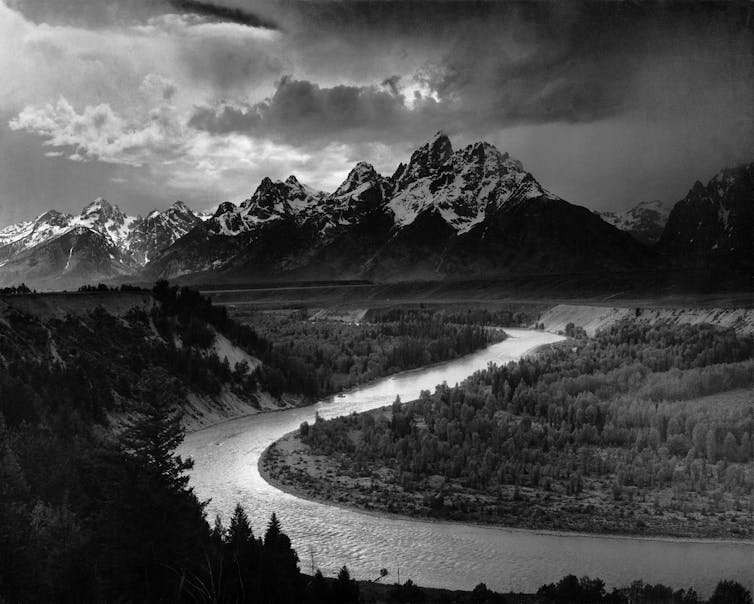

Landscape photography is a diverse genre, encompassing a wide range of contemporary practice. Yet, for many, iconic figures such as American photographer Ansel Adams embody what landscape photography is. His technically advanced images of the grandeur of nature are perfectly framed snapshots of near-other-worldly, untouched environments.

In a similar way, when we share landscape photos on Instagram, we often seek to show the beautiful, the staged, or the perfectly composed. We applaud these images, through liking and sharing them. And, conceivably, we increasingly picture nature as a similarly idealised aesthetic experience. We end up with very little visual diversity in how we present – and chose to experience – nature.

Instagram ultimately boils down to two people – the one who took the picture and the viewer. Perhaps it’s time for us as Instagram photographers to think a bit more deeply about the less exotic, but no less enchanting, places around us. We should challenge what we take photos of, and how we present nature. Nature, after all, is more than #trees and #clouds.

And, as Instagram viewers, we should think carefully about how we encourage different experiences of nature. Should we “like” the images and follow people and groups who clearly are pushing limits to both their own safety and the environment? Instagram is a fantastic social media tool to share the world – but it’s clear we need some perspective in using it.

Ellen Marie Saethre-McGuirk, Visiting Fellow (Assoc. Prof. Nord University), Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.