Rebecca Macmillan, University of Texas at Austin

Twenty-four percent of U.S. teens say they’re online “almost constantly.” Now much of that time, it seems, is spent incessantly compiling and navigating vast collections and streams of images.

In a 2014 survey, the photo sharing app Instagram supplanted Twitter as the social media platform considered “most important” by U.S. teens.

These results stayed the same for 2015, confirming just how crucial image sharing and consumption have become to young people’s everyday online experiences. Not surprisingly, Facebook and Twitter have since become more image-driven. And Snapchat – which enables users to create and share ephemeral photographs and short videos – is one of the fastest-growing social networks.

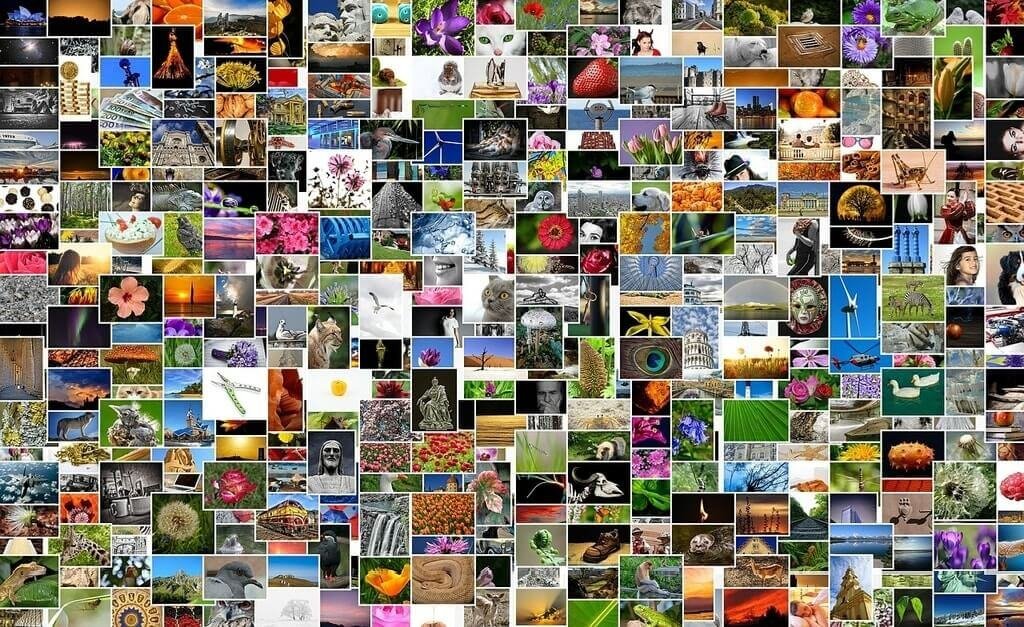

Indeed, our relationship with photographs is rapidly changing. As we snap, store and communicate with thousands of images on our phones and computers, a number of researchers and theorists are already beginning to point to some of the unintended consequences of this “image overload,” which range from heightened anxiety to memory impairment.

Overwhelmed – and distracted – by images

In the Rhetoric of Photography course that I’ve taught at the University of Texas at Austin over the past few years, image glut was a constant topic of discussion among my students.

They repeatedly expressed feeling overrun by photographs and addicted to posting images. They even waxed nostalgic about the clunky plastic cameras of their childhoods, wistfully recalling the days of limited exposures and a waiting period before seeing their developed prints.

“Images are produced, commodified, made public and circulated on an unprecedented scale,” sociologist Martin Hand writes in his book Ubiquitous Photography.

Image overload hinges on feeling visually saturated – the sense that because there’s so much visual material to see, remembering an individual photograph becomes nearly impossible.

For my students, this feeling was marked at times by general frustration, low-grade anxiety and flat-out fatigue. Image overload also suggests a level of exhaustion with the process of monitoring and creating photo streams – surviving the pressure to digitally document one’s everyday life and to bear witness to others’ ever-growing image banks.

Many accumulate thousands of images on their phones and digital cameras. The daunting task of organizing, altering and deleting these can evoke feelings of dread. Indeed, according to a 2015 report, the average smartphone user has 630 photos stored on his or her device.

Martin Hand also notes the “degrees of anxiety, concern and fascination” that his own students demonstrated in response to the daunting demands of public image proliferation and upkeep.

“Aside from anxieties about accidental deletion or irrevocable loss,” Hand continues, “people often express concern over the inability to organize, classify or even look at all their digital images in ways that are meaningful for them.”

Meanwhile, Fred Ritchin, the Dean of the School at the International Center of Photography, argues that the constant stream of visual information contributes to the kind of fragmented focus that former Microsoft executive Linda Stone calls “continual partial attention.”

In other words, by always being tuned in and responsive to digital technologies, we become less aware of our surroundings. As our attention succumbs to the allure of being someplace else, our concentration suffers.

Photo-taking memory impairment

According to psychologist Maryanne Garry, the overabundance of digital images may be detrimental to memory formation.

Garry argues that a constant flood of photographs doesn’t actively inspire remembrance or generate understanding. As Garry explains, narratives are crucial to memory formation. When viewing a barrage of images, unless there’s some sort of timeline, contextualization or intense focus, we’ll fail to place the image within an overarching story – and it becomes that much more difficult to retain the memory of the image.

Meanwhile, through her research, psychologist Linda Henkel has encountered what she describes as the “photo-taking impairment effect” – the idea that photographing may discourage remembering.

In Henkel’s study, students who visited an art museum with cameras in tow remembered fewer of the objects they photographed than those they simply observed. And if they did remember the photographed object, they were less likely to recall specific details.

However, a second study found that if a student took the time to zoom in on an object, their memory was not impaired – an indication that increased attention and cognitive engagement can counteract this effect.

Snapping photos in the here and now

During my third semester teaching The Rhetoric of Photography, I created an assignment to allow my students to explore their concerns about image overload.

Students would spend at least a week shooting with a disposable camera before developing their film and writing about the experience. I specifically asked them to comment on film scarcity, the inability to digitally manipulate or review images, the feel of the camera and the delay between shooting and seeing their photographs.

Reflecting on the disposable camera assignment, many students delighted in the deliberately slow pace of the process.

“Without the option to manipulate or review each of these photos, I had to think even further about the size of my frame, lighting orientation and subject proximity to the camera lens,” one student wrote. “Capturing in this way was satisfying and relaxing. Despite the fact that I could not alter or delete exposures, I had the opportunity to breathe and set up the perfect shot.”

Another commented, “While modern technology has given us the comfort of not having to physically move around as much to take a photograph, when you actually do it you feel more in the moment.”

Students seemed able to achieve the type of heightened focus that Henkel argues may enhance memories. Many students simply felt liberated. The pressure to alter an image until it was just right for public consumption was lifted.

The stress and anxiety my students routinely referred to speaks to the changing role of images, especially for younger generations. No longer do photographs primarily function as works of art or memorial objects.

Instead, as media Studies professor José Van Dijck explains in “Mediated Memories in the Digital Age”:

Even though photography may still capitalize on its primary function as a memory tool for documenting a person’s past, we are witnessing a significant shift, especially among the younger generation, toward using it as an instrument for interaction and peer bonding.

Part of what image overload may well register, then, is the regular pressure to communicate through photographs, which requires a series of ensuing steps beyond simply clicking the shutter: editing, posting, promoting, and responding.

At the end of the assignment, students had roughly 24 pictures to show for their week (fewer than some might post online in a typical day). But they came away with a clearer sense of their own patterns of perception and photographic engagement. They also gained confidence in their capacity to step back (if only slightly) from nonstop image feeds.

With photo streams continuing to proliferate, greater self-awareness can counteract feelings of drowning amidst a flood of images. And by engaging with analog technologies like disposable cameras, we’ll be better equipped to foster a slower, more intentional form of attention that’s crucial to defending our memories and sensations from being washed away.

Rebecca Macmillan, Ph.D. Candidate in English, University of Texas at Austin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.