By Liani Maasdorp, University of Cape Town

South Africa’s film industry is the oldest in Africa and one of the oldest in the world, having started in 1896, soon after the Lumiere brothers’ famous first commercial film screening in 1895. The industry is one of the more established and commercially viable on the continent.

It doesn’t produce as many films as Nigeria’s bustling industry, but offers a steady trickle of crowd pleasers (with box office records held by the comedies of Leon Shuster) and international award winners like Tsotsi (2006) and Skoonheid (Beauty, 2011). There remains an existing, loyal, cinema-going audience for Afrikaans productions, but films in other local languages, even critically acclaimed ones with high production values, have not been very profitable.

The industry is normally worth around R3.5 billion to the economy annually. In 2019, 22 South African films received a local cinema release, claiming only R60 million of the R1.2 billion taken at a local box office dominated by Hollywood fare.

The most lucrative form of production in post-apartheid South Africa has been what’s called facilitation. Many South African producers specialise in hosting international film and TV productions by providing crews, finding locations and casting extras for clients. The film incentives offered by the Department of Trade and Industry allow visiting productions to claim money back for working in the country and have helped make it one of the more attractive film destinations globally.

The COVID-19 pandemic has, of course, put a halt to this. As in other countries, the pandemic has hurt the industry. Just because lockdown regulations were relaxed for film and television production in April doesn’t mean it’s been back to business as usual. There are strict operating directives and only 50 individuals are allowed on set or location at a time, limiting the size and complexity of productions that can be completed.

But there are several dynamics that had already begun prior to the lockdown that have been brought to the fore by the radical reduction in production. These include micro-budget filmmaking, alternative distribution methods and collaborative film projects. They could be among the keys to unlocking further growth in the industry in the future.

High value from low budgets

Enter the micro-budget film. Cape Town-based writer-director-cinematographer Jenna Cato Bass is a pioneer in this area. At 34, she has already directed three features – urban romance drama Love the One You Love (2014), “body-swap satire” High Fantasy (2017) and “feminist western” Flatland (2019). In a recent interview she told me she wants to “make a career making films and would like to make many of them”.

Her films are made by small crews on tight budgets. They don’t feel like, or compete with, slick big budget Hollywood films. Yet, they have a niche following, consistently premiere at top international festivals and she keeps getting funding to make more of them.

Though she had to postpone shooting her fourth feature film due to the lockdown, she says she will recover. Because her production costs are low, she can postpone her shoot. And because her crews are small, she can start shooting while personal distancing restrictions gradually lift. This puts her at a distinct advantage over multi-million dollar productions.

Lockdown breeds collaboration

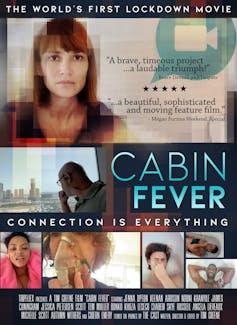

Another trend has been the production of content remotely. Several collaborative productions were initiated almost immediately after the country’s lockdown started. These included the Tim Greene-led production Cabin Fever. For this co-authored fiction film, actors performed scenes at home, filming themselves on whatever camera or device they had access to. The footage was then uploaded for editors, also working from home, and director viewings are done remotely using platforms like the now ubiquitous Zoom.

Remote filmmaking makes it possible to keep producing films by optimising on a collective of different creatives’ skills, equipment and software. It also capitalises on creative collaboration – which had already been a feature of local production, especially documentaries – and reduces the notoriously large carbon footprint of filmmaking.

Online distribution

Most of Bass’s films are available on streaming service Showmax from local satellite entertainment giant MultiChoice. Showmax seems to be prioritising acquiring local content – licensing as many as they can, as quickly as they can. These include acclaimed features Five Fingers for Marseilles (2017), Inxeba (The Wound, 2017), Kanarie (2018) and Sew the Winter to My Skin (2018).

But Showmax is not the only way to get a film into people’s homes. South African filmmakers have been exploring independent distribution models for a while. The latest film from the critically acclaimed Oliver Hermanus, Moffie (2019), was scheduled for cinema release just as the lockdown started and public screening venues shut down. The film premiered in Venice in 2019 and the producers understandably did not want to delay until 2021 to get it to local audiences. It’s now streaming directly from their own website on a pay-per-view basis, using their own platform and ticketing service, OneTix. They felt it “made more financial sense” Hermanus told me.

Reportedly Showmax offers around $5 000 for a non-exclusive 18 month license for a feature film, so it’s understandable that filmmakers would use independent platforms to connect films to viewers directly. But by mid-2018 Showmax had almost 600,000 subscribers, outperforming global giant Netflix’s local offering. A bespoke platform would struggle to reach that number of viewers without an extensive and well-resourced marketing campaign.

Making and distributing films in new ways, that are also cognisant of the global climate emergency, is going to become a growing trend not just in South Africa, but around the world. As we recover from the impacts of the pandemic, we will also take stock of the positive effects #stayhome has had. In South Africa that includes inspiring or enhancing innovative ways of creating and sharing films.

This article is an expanded version of a story that first appeared in 8 ½, an Italian film magazine published by Istituto Luce.

Liani Maasdorp, Senior lecturer in Screen Production and Film and Television Studies, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.